When one of our kids was a toddler, he had a habit I feared would become a problem as he got older. There is a history of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in my family and I worried that his habit was a forerunner of it. I called the most prominent pediatric behavioral specialist in the country, a man whose books made him a household name, both within the pediatric community and among parents in the real world. I reached him quickly by phone—announcing that I was a physician usually got me through the gatekeepers and directly to any colleague I was trying to reach. In this case, I knew of the famous man, but he didn’t know me. He picked up and said, “This is Dr. X, how can I help you?” I briefly explained my concerns about my toddler and asked if I should be worried. I’ll never forget the words he said or the tone he said them with: “Dr. Rotbart, if I gave phone advice to every physician-parent who called me, without seeing the child for a proper evaluation, I would never get anything done. I suggest you find a pediatrician locally who can help you with this. Have a nice day.” It’s hard to adequately describe the hurt this famous pediatrician caused me.

Several hours later, recovered from the first experience, I called another famous person in the field of developmental pediatrics, a well-known psychologist, and the author of as many books as the famous pediatrician. As with the famous pediatrician, this was a complete “cold call.” Dr. Louise Bates Ames also picked up the phone quickly and asked how she could be of help. I didn’t know Dr. Bates Ames and she didn’t know me. I repeated the same question I had asked the famous pediatrician.

Dr. Bates Ames then spent nearly an hour on the phone with me, asking questions and getting details, and then reassuring, comforting, and explaining the fluctuating stages of childhood development that often revealed concerning, yet perfectly normal, phases of a child’s growth. Our son’s behaviors were common and not worrisome. They would disappear, she predicted, within six months or less. If that period passed and I was still concerned, or if I had questions before that, she insisted that I call her again to revisit the issue. In the meantime, she suggested the best course of action was to neither call attention to the behavior nor ask our son to stop. She advised we ignore the behavior as it wasn’t causing our son or anyone else any harm. Ignoring, rather than focusing on, behaviors like this was a much more effective strategy to speed their resolution.

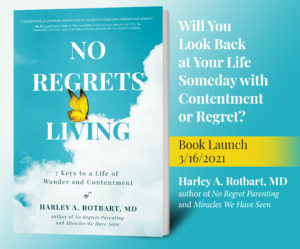

We did exactly as she said, and so did our son, whose worrisome habit was gone within a couple months. Dr. Bates Ames passed away eight years later. I grieved when I read the news because I know how many parents’ lives she touched with her gentle and patient wisdom. Hers was a kindness to a stranger that I have tried to repay throughout my career whenever concerned colleagues, whether I knew them or not, called me about their own children. I hope I’ve done as good a job for others as Dr. Bates Ames did for my family, now more than thirty years ago, but I am certain I’ve never treated anyone the way that famous pediatrician treated me. I don’t know if that famous pediatrician was capable of feeling regret, but I doubt he ever felt the rich rewards Dr. Bates Ames surely felt for the kindnesses she showed during her career . She is another poster child in my life for No Regrets Living, an important role model for my career, and one of those to whose memory I’ve dedicated my No Regrets Living book.