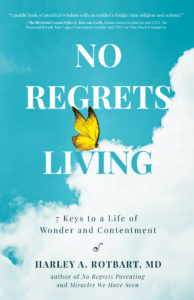

I’ve written a book called “No Regrets Living – Seven Keys to a Life of Wonder and Contentment” which outlines the critical steps toward living a life with fewer regrets. But here’s a confession: I haven’t succeeded in totally preventing regrets or purging the regrets I already have. As I note in the book, there’s really no such thing as “No Regrets Living,” but there are ways to minimize the regrets we develop and heal from those we already have. That’s what the book is about. That said, the book also confesses some of my personal regrets. Here’s one example.

Several years ago, my wife’s sister and brother-in-law invited us to take a trip to Tanzania with them for a safari experience. My wife joined them, I couldn’t. During three decades in medicine, I had many opportunities to travel abroad to volunteer in underserved parts of the world where a pediatrician’s skills could be life-altering, even lifesaving, for those in greatest need. I didn’t have the courage to do it, and I’ve had regrets ever since. As an infectious diseases doctor at Children’s Hospital, I cared for some of the sickest children in the U.S. – kids with devastating infections complicating devastating underlying diseases. And that work was very fulfilling for me, even during the many sad moments when our best efforts failed. At least I was in the fight. But my insecurity with my general pediatric skills, skills which I hadn’t practiced since residency training and which would be required in international clinic environments, prevented me from traveling to those clinics and trying. In retrospect, that was unfounded insecurity. Even though my day-to-day practice of pediatrics was limited to the sickest kids requiring the most intensive care, I’m certain enough of my basic pediatric knowledge would have resurfaced as patients in Haiti or the Dominican Republic or Africa would have required. Instead, I stayed home, worked diligently on tough cases, but slept in my own bed at night and didn’t push myself beyond my comfort zone. And I have felt regret ever since. And guilt. Guilt which spoke to me with these words, “when you had the chance to be in Africa to make a difference, you didn’t go. Now you want to visit as a tourist, an elitist, a voyeur? To enjoy the beauty of the land and ignore the poverty and disease you did nothing to change?” I didn’t feel like I had earned a vacation adventure in Africa. I regretted what I hadn’t done, the opportunities I missed to make a small dent in parts of the world that need so much. Guilt and regrets are closely related.

When regrets and guilt affect our decisions, it’s time to re-examine the source and substance of those feelings in hopes of self-forgiveness. There are enough redeeming actions and exculpatory reasons to have allowed me to forgive myself and move on.

You may be wondering why I don’t go to Africa (or Haiti, or the Dominican Republic or Puerto Rico) now, making amends in arrears for my lack of courage when I was younger. A good question. Now, even more removed from the day-to-day practice of pediatrics, and older enough that health issues have crept in, it remains a difficult decision for me – but I’m working on it.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy my clinical psychologist daughter has taught me about. It is a methodology psychologists use to treat some of their most challenging and difficult patients, especially those with self-harming or suicidal thoughts. DBT helps patients to both accept who they are, recognizing the issues and behaviors which trouble them, while also guiding patients to change those behaviors and resolve those issues. The therapy teaches clients to wholly accept themselves and their troubling behaviors while simultaneously working to change them. For those of us fortunate enough to have less severe challenges to overcome, seeking self-forgiveness asks us to use a similar approach – recognize and accept what’s causing our regrets and guilt and find emotional and practical ways to move forward.