AN EXCERPT FROM MY NEW BOOK, “NO REGRETS LIVING” ABOUT DAD, MOM, AND WHAT IT MEANS TO BE TRULY RICH.

I’m the child of a Holocaust survivor. I grew up in a home under the shadow of the most unspeakable evil the modern world has ever known, daily asking myself how something like that could happen to my father, his family, and millions of others. My father was arrested by the Nazis on August 6, 1941, at age seventeen and transported to a variety of labor and concentration camps, finally ending up in Auschwitz two years later, on August 28, 1943. There, he was tattooed with the number 142178. This information is part of the precise and elaborate record-keeping by the Nazis known as Häftlingspersonalbogen, or prisoner registration forms, the bane of existence to every Holocaust denier in the world. These records, kept by the Nazis themselves and now magnificently archived in the US Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC, prove, beyond any doubt, the unparalleled efficiency and evil of the Nazis.

After his arrest, my dad never saw his mother or sister again; they were transported to concentration camps and killed. His father, Hersh, after whom I’m named, was arrested with my dad. Those like my father and his father, strong enough to be valuable as laborers, were not immediately sent to the gas chambers. As my dad’s father became progressively weaker, my dad tried to do the work for both of them so the Nazis wouldn’t notice his father’s debilitation. Ultimately, they did notice and his father, no longer useful to the Nazis, was taken to the gas chamber.

I don’t know much more about my dad’s concentration camp experience—it’s a known syndrome among survivors that they were hesitant to share those memories with their loved ones to spare them the pain. But it’s also a known syndrome among survivors’ kids that we don’t ask enough, afraid of what we might hear and afraid of ripping open our parents’ fragile emotional scars (the groundbreaking work on this subject is Helen Epstein’s Children of the Holocaust (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1979).

I regret not having asked more, and because my father died forty years ago, that’s a regret I can’t fix. After liberation from the camps and while working in an underground railroad helping to smuggle fellow survivors into Israel, Dad developed tuberculosis and was hospitalized in Czechoslovakia. His subsequent immigration papers sent him to Denver, probably because the high altitude and dry air were felt to be beneficial in recovering from TB.

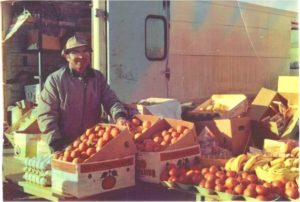

On arrival in America, penniless, without family, and not speaking a word of English, Dad’s story of survival continued. He met Mom at a resettlement center where she served as a translator for the Yiddish-speaking immigrants. Needing to make a living, Dad began selling fruits and vegetables in a truck borrowed from my mom’s uncle. Mom rode the truck as well, translating kartoffel and tsibele into “potatoes” and “onions” for dad’s customers. Dad was the most brilliant fruit peddler in the history of fruit peddling, the smartest man I ever knew. We grew up very poor, but we never knew it. My dad’s survival and entrepreneurial skills, and my mom’s frugality and morality, taught us vital life lessons about the true definition of the word “rich.”